Center of Excellence in Newcomer Health

- Minnesota Center of Excellence in Newcomer Health Home

- About

- Clinical Guidance and Clinical Decision Tools

- Health Education

- Publications and Presentations

- Trainings

- Newcomer Health Profiles

Spotlight

Somali Refugee Health Profile

Last updated: March 2024

Last updated: March 2024

On this page:

Priority health conditions

Background

Population movements

Health care access and health conditions among Somali refugees prior to arrival in U.S.

Medical screening of U.S.-bound refugees

Health conditions to consider during post-arrival medical screening

References

Priority health conditions

Somali refugees have been resettled for many years in communities across the United States. The information in this refugee health profile is intended to help resettlement agencies, clinicians, and public health providers understand the health issues of greatest interest or concern pertaining to Somali refugee populations in the United States, as well as their cultural background and circumstances of their displacement.

The health conditions listed below are considered priority health conditions in caring for and assisting Somali refugees. This combination of health conditions represents a distinct health burden for the Somali refugee population. More information is available in the dropdown sections below.

- Anemia

- Diabetes mellitus

- Female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C)

- Lead toxicity

- Schistosomiasis and strongyloidiasis

- Viral hepatitides (hepatitis B and C)

Background

After gaining independence from Italy and Great Britain in 1960, Somalia was a stable nation. However, political instability in the early 1990s resulted in a protracted humanitarian crisis and an ongoing, territorial civil war. Recent elections have been largely peaceful and shown signs of progress, but Somalia remains deeply divided by insurgent groups and rival militias. The civil war, coupled with extreme famine (particularly in rural areas), unequal distribution of aid, and poor economic prospects, has led to the mass exodus and diaspora of Somalis worldwide.1

The Federal Republic of Somalia (hereafter referred to as Somalia), is located in Eastern Africa and is part of the Horn of Africa, a large peninsula that juts into the Arabian Sea (Figure 1). Somalia borders Kenya, Ethiopia, and Djibouti, as well as the Gulf of Aden and the Indian Ocean. Although Somalia has a largely desert climate, parts of the country experience seasonal monsoons. The country is prone to recurring droughts, frequent dust storms in the eastern plains, and flooding during the rainy season. Famine, deforestation, overgrazing, soil erosion, and desertification have become major issues in recent decades.2

Figure 1: Map of the Horn of Africa

Ethnic Somalis are unified by culture, language, religion (Islam), and common Samaale ancestry. Persons of Somali origin account for approximately 85% of the population, while minority ethnic groups account for the remaining 15%.2 The largest ethnic minority in Somalia is the Somali Bantu, whose ancestral origins include, among others, the Makua, Yao, Ngindo, and Nyasa of Tanzania, Mozambique, and Malawi.3 Many Bantu trace their origins to ancestors from these southeast African tribes who were enslaved and brought to Somalia during the 18th century [3]. Minority ethnic groups also include Bravanese (Barawa) and Rerhamar (Arab descent); Bajuni (originating from the East African coast); as well as the Galgala, Tumal, Yibir, Gaboye, and Eyle.4

Ethnic groups in Somalia can be further divided into clans. Clans are socially and politically important, and membership is determined by paternal lineage.5,6 Majority (Somali origin) members (or “nobles”) belong to one of four patrilineal clans: Darod, Hawiye, Dir, and Rahanweyn (Digil-Mirifle). These clans largely dominate modern government and politics, as well as the economy and urban life.5 Somalia’s minority clans are incredibly diverse, and are defined not solely by ethnicity, religion, or linguistic variances, but also by social and historical distinctions.5 Minority clans are derived from minority ethnic groups. Minority clans include Bantu, Bravanese (Barawan), Bajuni, Eyle, Galgala, Tumal, Yibir, and Gaboye.4 Minority clans often live in poverty, and many suffer from discrimination and exclusion. Insufficient numbers of health centers in regions where minorities live and lack of public transit infrastructure often prevent minorities from accessing critical health care services.4

Clans are a very sensitive topic for many Somalis. Enduring tension between rival clans has been a major factor in the ongoing conflict in Somalia. Clinicians should avoid discussing clans with Somali patients as many may find it disrespectful or offensive.6

Somali is the primary official language. There are two main Somali dialects: Standard Somali and Digil/Raxanweyn Somali. Standard Somali is spoken by most Somalis, while the Digil/Raxanweyn dialect is spoken primarily in Shabelle and Juba river valleys in the south.7 However, Standard Arabic is also an official language (according to the Transitional Federal Charter).2 Italian and English are common, and Swahili is also spoken in regions in southern Somalia.2,7 Indigenous languages include Maay, Oromo, Borana-Arsi-Guji, Dabarre, Garre, Jiiddu, Mushungulu, Tunni, and Boon.8

Civil war resulted in a complete breakdown of the formal education system in Somalia. Somalia has one of the world’s lowest enrollment rates for primary school-aged children, where as few as 25% of children have access to primary education, and secondary school enrollment is estimated at 6%.9 Of note, school enrollment in Somalia is substantially higher for boys than girls.7 Educational opportunities for Somalis are also limited in countries of asylum. In the Dadaab Refugee Complex in Kenya, access to quality education is severely limited. The number of school-aged children in Dadaab far exceeds the capacity of schools, and schools lack adequately trained teachers and learning resources.10

Literacy among Somalis is low. Among adults (15 years of age or older), male literacy is approximately 49.7%, while literacy among women is substantially lower at 25.8%.9

The provisional federal constitution of Somalia recognizes Islam as the state religion and requires that all laws must comply with the general principles of sharia.11 Nearly all Somalis are Sunni Muslim, and it is estimated that less than 1% of the total population belongs to other religious groups (e.g. Christian, Shia Muslim).2,11

Somali society tends to be patriarchal, and men and women are generally separated in most spheres of life. Men often act as the head of the household and work outside the home, while women usually manage the home and raise children. Family is extremely important; Somali culture is more focused on the family than on the individual. It is not uncommon for extended families to live together.6 Elders are venerated within the Somali community, and their counsel is sought for personal and community issues.6 In some communities, arranged marriages may be common. Some Somalis may practice polygamy; men may have multiple wives, if they can afford to do so.6

The majority of Somalis, particularly those who have lived in urban areas, have had some experience with Western medicine. Providers should ask new arrivals about past experiences with Western medicine, as well as their opinions of Western medical practices.12 However, some Somali refugees may be unfamiliar with routine preventative care, such as prenatal or well-child care.6 Additionally, many Somalis have had experience with traditional healers. Traditional healers use a variety of methods including fire-burning (a procedure where a stick from a special tree is heated and applied to the skin to cure illness), herbal remedies, and prayer. They employ these methods to treat a variety of illnesses such as viral hepatitis, measles, mumps, and varicella (chickenpox), and may be familiar with treating hunchback, facial droop, and broken bones. Traditional doctors are believed to have the ability to cure illnesses caused by spirits.6

Like most populations, Somalis tend to have specific care preferences, attitudes, and expectations driven by cultural norms and religious beliefs [6]. However, individual interpretations of Islam and diverse cultural practices require healthcare providers to address views and preferences of each refugee.13

While there are no universal Islamic health care practices or preferences, Somali Muslims (who account for roughly 99% of the Somali population) may be more likely than the general U.S. patient population to:

- View the health of each individual as a family concern13

- Accompany family members, especially wives and children, to medical appointments13

- Prefer a healthcare provider and/or interpreter of the same sex13

- Feel uncomfortable disclosing health information to strangers, potentially making initial diagnosis difficult13

- Express concern regarding vaccine safety, particularly with childhood measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccination14

- Be unfamiliar with chronic diseases and the need to take medication for a long time12

- Use herbs and other traditional medicines provided by traditional healers12

- Consult traditional and spiritual healers about mental health issues12

- Have dietary restrictions and avoid consuming pork products, medications with pork ingredients (common in gel formulations), and meat that is not Halal*13

- Abstain from alcohol6

- Request vegetarian meals in hospitals, or have family bring meals during hospital stays13

- Fast (avoid food, water, and medicine from dawn to dusk) during the month of Ramadan and may opt to take medications before dawn or after dusk to avoid breaking fast13

*Halal is Arabic for “lawful” or “permitted” and refers to how meat is butchered in accordance with Islamic law.

When possible, providers should ask patients if they prefer an interpreter who is of the same ethnic background or gender.

For more information about the orientation, resettlement, and adjustment of Somali and Somali Bantu refugees, please visit EthnoMed: Somali.

Population movements

Somalia is considered a globalized nation, with more than 1 million Somalis currently living outside the country. Somalis are largely concentrated in three areas: the Horn of Africa and Yemen, Gulf States, and Western Europe and North America.15 Nearly two-thirds of all Somalis living outside Somalia live in neighboring countries, namely Kenya, Ethiopia, Djibouti, and Yemen.16 In Europe, the United Kingdom is home to the largest Somali community, followed by the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, and Denmark.15 A growing number of Somalis have also settled in Switzerland, many of whom arrived as asylum seekers.16 Lastly, Malaysia and Australia have also seen an influx of Somali immigrants in recent years.15 In the United States, Minnesota is home to the largest Somali community, with the majority residing in the Minneapolis-St. Paul metropolitan area (Hennepin and Ramsey counties), as well as St. Cloud and Rochester.17 Many Somali refugees and immigrants have also settled in the Seattle metropolitan area, as well as Columbus (Ohio) and the surrounding area.14,18

As of December 2016, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimated that more than 1.5 million Somalis were internally displaced. Additionally, as of January 2018, more than 875,000 Somalis were registered with UNHCR as refugees in Africa and the Middle East.19,20 However, this figure only accounts for registered refugees, and therefore likely underestimates the scale of the refugee crisis in the Horn of Africa. Kenya, Ethiopia, and Yemen host the largest numbers of Somali refugees. Somali refugees have also fled, in smaller numbers, to Djibouti, Egypt, Eritrea, Uganda, and South Africa.20

Kenya hosts the largest number of Somali refugees (more than 313,000 as of April 2017), most of concentrated in the Dadaab Refugee Complex, in Garissa County near the Somali border. Established in 1991 to provide refuge for families fleeing the Somali Civil War, Dadaab consists of four camps: Dagahaley, Hagadera, Ifo, and Ifo 2. A fifth camp, Kambioos, was closed in February 2017. As of April 30, 2017, UNHCR estimated that approximately 245,000 Somali refugees live in Dadaab [20]. Other sources estimate that between 300,000 and 350,000 Somali refugees reside in Dadaab, as many refugees in the complex are not registered with UNHCR.21,22 Some camp residents have lived in Dadaab for more than 20 years, while many others were born in the camp and have never set foot in Somalia. Additionally, as of April 2017, approximately 40,000 Somali refugees were living in Kakuma Refugee Camp, located in northwest Turkana County, and more than 30,000 Somali refugees were living in Nairobi.20

As of March 2018, more than 255,000 registered Somali refugees were living in Ethiopia. At that time, more than 217,000 Somali refugees lived in Dollo Ado Refugee Complex, which consists of five camps: Bokolmanyo, Melkadida, Kobe, Buramino, and Hilaweyn. At the end of March 2018, roughly 37,000 Somali refugees resided in the Jijiga Refugee Complex, consisting of three camps: Aw-barre, Kebribeyah, and Sheder. Additionally, UNHCR reports that fewer than 1,000 Somali refugees live in Addis Ababa. However, the true number of refugees in Addis Ababa is likely much higher, as UNHCR estimates only account for registered refugees.20

While the majority of Somali refugees have sought asylum in either Ethiopia or Kenya (exceeding 567,000 total refugees), more than 255,000 Somali refugees have been registered in Yemen as of December 2017 [20]. Somali refugees have been arriving steadily by boat in Yemen since 1991, via the Gulf of Aden [23]. Some Somali refugees go to Kharaz Refugee Camp. However, Kharaz is too small and underresourced to accommodate the number of new arrivals; therefore many remain in urban areas such as Sana’a.23,24 In Yemen, Somali refugees often live in poverty, have difficulty finding work, and are at increased risk of human trafficking and discrimination. Some Somalis try to reach Saudi Arabia for better employment opportunities.20

For up-to-date information regarding Somali refugees in the Horn of Africa and Yemen, please visit UNHCR’s Information Sharing Portal for refugees in the Horn of Africa Somalia Situation.

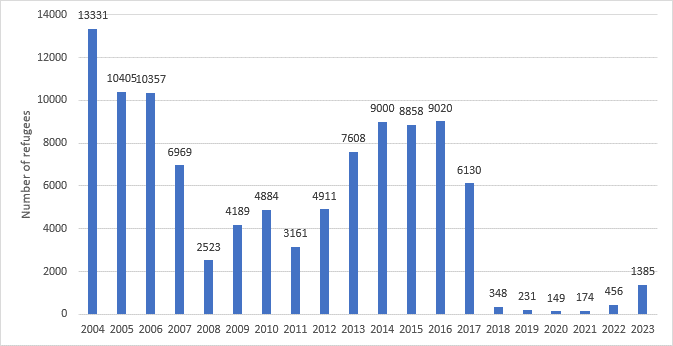

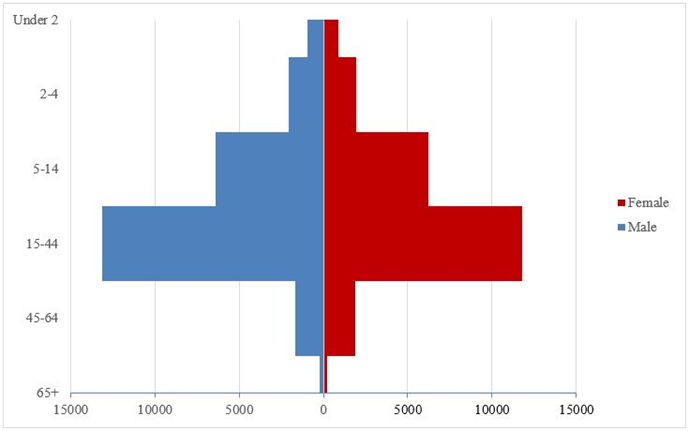

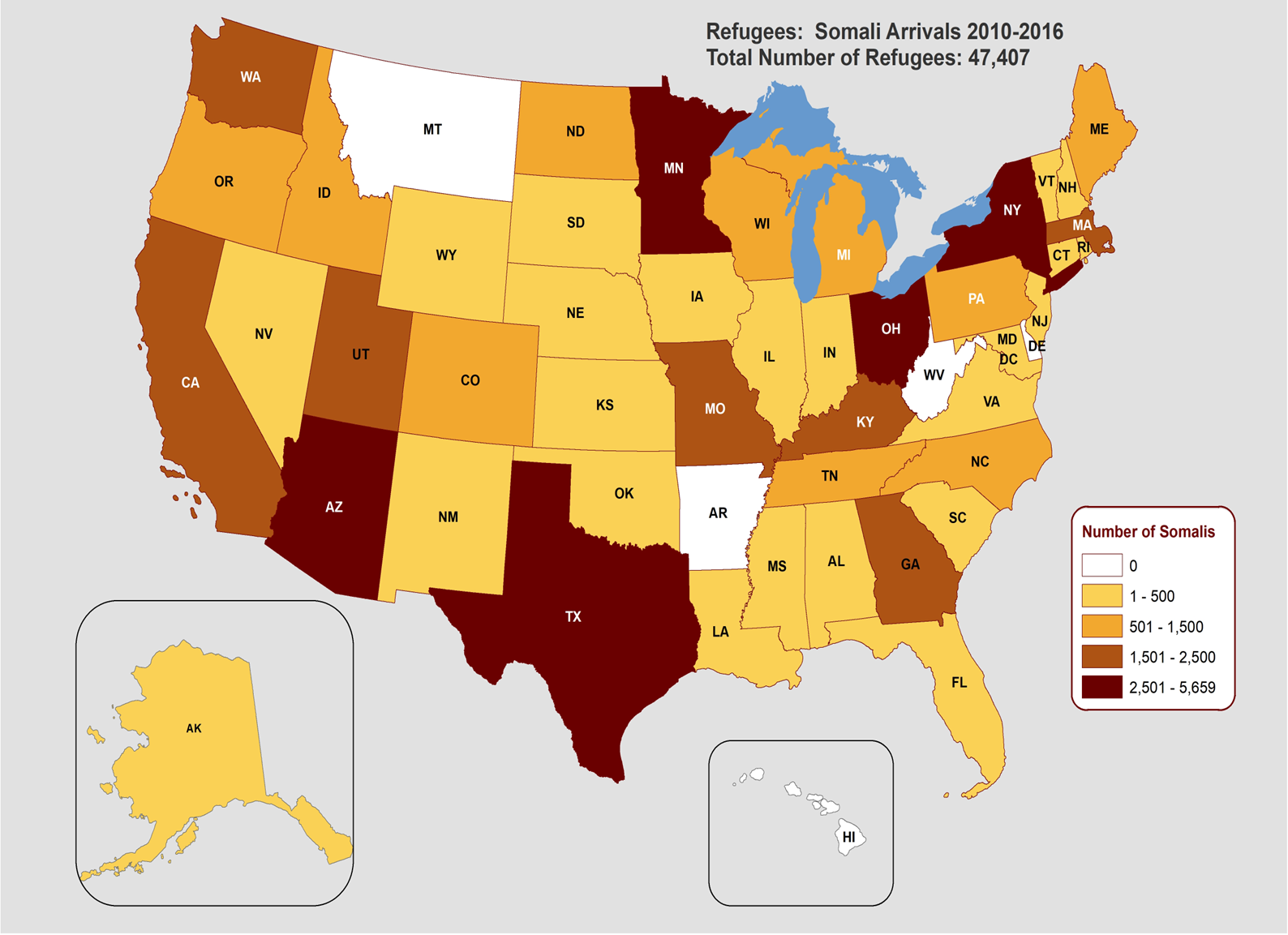

Resettlement of refugees from Somalia first began in 1990. The number of Somali refugee arrivals nearly tripled between 2011 and 2014.25 From 2001 to 2023 (fiscal years, October 1 to September 30), more than 111,000 Somali refugees arrived in the United States (Figure 2), with the majority of arrivals under 45 years of age and roughly equal numbers of male and female (Figure 3).25 During this time, Minnesota and New York welcomed the largest numbers of Somali primary refugee arrivals, followed by Texas, Arizona, Ohio, and Washington (Figure 4).26

Following initial resettlement in the United States, many Somali refugees relocate to states with well-established Somali communities. Minnesota receives a significant number of secondary refugee arrivals, with the largest numbers coming from New York and Texas. From 2010 to 2016, the Minnesota Department of Health (Refugee Health Program) was notified of 3,740 secondary arrivals.17 However, the true number of secondary Somali arrivals is likely much higher, as the state is not always notified. The majority of secondary arrivals in Minnesota settle in Hennepin, Stearns, and Kandiyohi counties, all of which have well-established Somali communities.17

Figure 2: Somali Refugee Arrivals in the United States, Fiscal Years (FY)* 2004–2023 (N=47,407)

Source: Worldwide Refugee Admissions Processing System (WRAPS)25

*U.S. fiscal year begins October 1 and continues through September 30 the following calendar year

Figure 3: Age Distribution for Somali Refugees at Time of Resettlement to the United States, FY 2010–2016 (N=47,407)

Source: Worldwide Refugee Admissions Processing System (WRAPS)25

Figure 4: States of Primary Resettlement for Somali Refugees, FY 2010–2016 (N=47,407)

Table 1: States of primary resettlement for Somali refugees

| States | Number | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Minnesota | 5,659 | (11.9) |

| New York | 3,786 | (8..0) |

| Texas | 3,620 | (7.6) |

| Arizona | 3,250 | (6.9) |

| Ohio | 2,834 | (6.0) |

| Washington | 2,422 | (5.1) |

| Missouri | 1,885 | (4.0) |

| Massachusetts | 1,781 | (3.8) |

| Georgia | 1,725 | (3.6) |

| Kentucky | 1,693 | (3.6) |

| California | 1,613 | (3.4) |

The remaining 17,139 refugees were resettled in 34 different states across the United States, as well as the District of Columbia.26

Source: Worldwide Refugee Admissions Processing System (WRAPS)26

Health care access and health conditions among Somali refugees prior to arrival in U.S.

Nonprofit organizations often provide health services to Somali refugees living in refugee camps and urban areas. Programs include water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) initiatives, primary and secondary health services, maternal and newborn services, tuberculosis (TB) treatment, and initiatives to address and reduce sexual and gender-based violence.27 In some settings, such as Dadaab Refugee Complex in Kenya, various outpatient services include consultation clinics, specialized and tertiary care, emergency medicine, as well as laboratory and pharmacy services.27 Limited mental health services are available.27 Refugees living outside refugee camps, particularly those not registered by UNHCR, may not have access to services in countries of asylum because they lack legal status, inability to obtain a residency permit, or inability to pay.

Some Somalis may have been vaccinated prior to displacement through national immunization campaigns. In Kenya, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), often supported by the Ministry of Health, may provide immunizations. Additionally, U.S.-bound Somali refugees may receive select vaccines as part of the voluntary Vaccination Program for US-bound Refugees depending on the country of processing (see Vaccination Program for U.S.-bound Refugees for additional information). However, Somali refugees generally have not completed the full Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)-recommended vaccination schedule before departing for the United States.

In Somalia, maternal and infant mortality rates are among the highest in the world. The maternal mortality ratio for Somali women is 732 deaths per 100,000 live births, while the infant mortality rate is estimated at 96.6 neonatal deaths per 1,000 live births.2,28 The fertility rate among Somali women is also high, with the average woman giving birth to 6.4 children during her life.29 The prevalence of contraception use is unknown.

Reproductive health data are extremely limited among Somali refugees. Generally, fertility rates among Somali refugees are high, and high rates of maternal mortality are exacerbated by a lack of awareness of the dangers of frequent childbirth and pregnancy at an early age. Even when reproductive health, family planning, and gender-based violence education and clinical services are available, utilization is often low.30

Health care providers in Dadaab and Kakuma report that many camp residents lack a basic understanding of reproductive health practices, family planning methods, preventative health services, and antenatal care.31 Although UNHCR-registered refugees in Yemen are allowed to use healthcare services, refugees often have difficulty accessing necessary care, the quality of care is largely insufficient, and public services are overburdened.30

Female genital mutilation/cutting

Female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) is defined as the partial or total removal of female genitalia or other intentional injury to female genital organs.32 Despite many countries having passed or drafted legislation banning FGM/C, global advocacy to end the practice, and lack of validation in Islam, FGM/C remains ingrained in Somali culture.32,33

In Somalia, FGM/C prevalence is estimated to be as high as 98% [34]. Infibulation (Type III), the most severe form of the procedure, is most common in northeastern Africa, including Somalia.35 FGM/C is also well documented in neighboring countries where Somali refugees have sought asylum. The prevalence of FGM/C among girls and women aged 15–49 years is estimated at 19% in Yemen, 21% in Kenya, 74% in Ethiopia, 83% in Eritrea, and 93% in Djibouti.34 Ethnicity is the most significant predictor for FGM/C. Ethnic groups often adhere to traditional cultural norms, including FGM/C, regardless of where they live. For example, among ethnic Somalis residing in Kenya, 98% of women and girls are believed to have undergone the procedure. This prevalence mirrors estimates in Somalia, yet far exceeds the reported national prevalence in Kenya.36

There is a large body of scientific literature on FGM/C, as well as best practices in gynecological care for FGM/C survivors. These publications may be helpful to clinicians and others working with Somali women:

- Johnson-Agbakwu CE, Flynn P, Asiedu GB, Hedberg E, Breitkopf CR. Adaptation of an acculturation scale for African refugee women. J Immigr Minor Health 2016 Feb;18(1):252–62.

- Johnson-Agbakwu CE, Allen J, Nizigiyimana JF, Ramirez G, Hollifield M. Mental health screening among newly arrived refugees seeking routine obstetric and gynecologic care. Psychol Serv 2014 Nov;11(4):470–6.

- Johnson-Agbakwu CE, Helm T, Killawi A, Padela AI. Perceptions of obstetrical interventions and female genital cutting: insights of men in a Somali refugee community. Ethn Health 2014 Aug;19(4):440–57.

- Lazar JN, Johnson-Agbakwu CE, Davis OI, Shipp MP. Providers’ perceptions of challenges in obstetrical care for Somali women. Obstet Gynecol Int 2013;2013:149640.

- Public Policy Advisory Network on Female Genital Surgeries in Africa. Seven things to know about female genital surgeries in Africa. Hastings Cent Rep. 2012 Nov-Dec;42(6):19–27.

Sexual and gender-based violence

Sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) is ongoing and has been used as a weapon of war in Somalia. In Somali society, rape victims are highly stigmatized and sexual assaults often go unreported. After an assault, survivors may isolate themselves, largely withdrawing from social life. Additionally, the health complications resulting from SGBV can be severe. Sexual assault can lead to pregnancy complications, as well as mental health issues including anxiety disorders, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and somatic symptoms.37

While refugee camps in countries of asylum provide some security and basic services, camp settings can increase the risk of SGBV. Lack of livelihood opportunities often forces women into poverty and situations where exploitation and abuse are increasingly common. Additionally, women are often responsible for obtaining food and firewood, drawing them away from secured areas. Lastly, insufficient police presence and high staff turnover negatively impact support services available to refugees.38

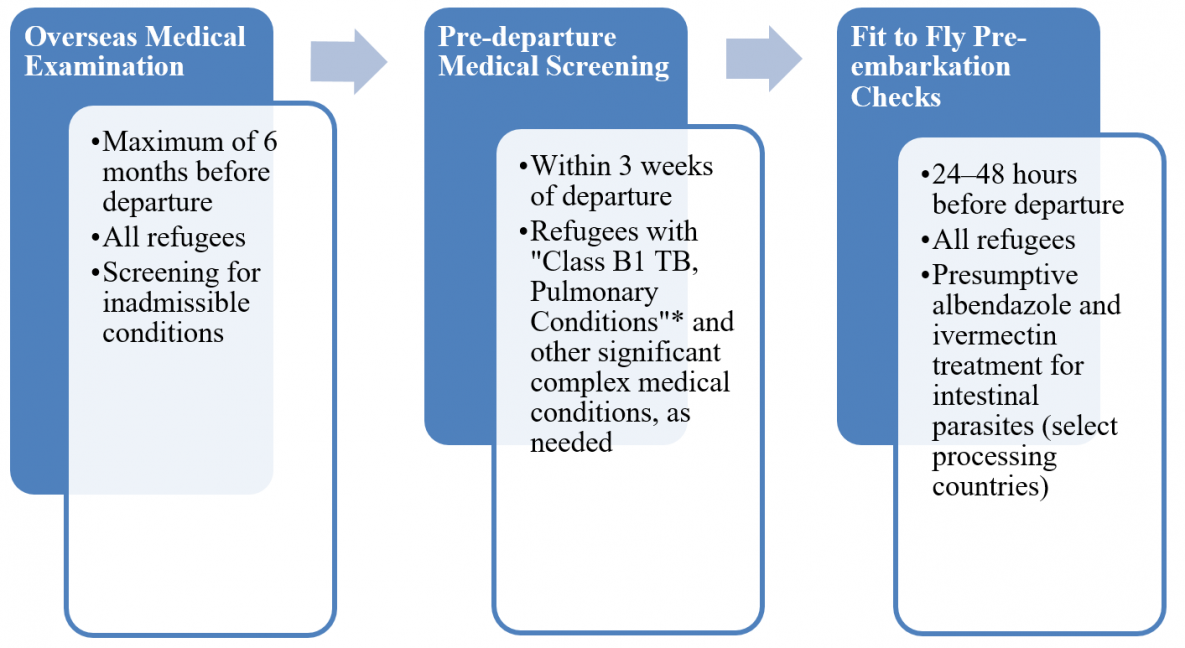

Medical screening of U.S.-bound refugees

Somali refugees who have been identified for resettlement to the United States receive a required medical examination. Depending on the country of processing, refugees may receive additional health checks (Figure 5). As outlined below, the full required medical examination occurs 3 to 6 months before departure; the pre-departure medical screening (PDMS) and pre-embarkation checks (PEC), if conducted, occur closer to or immediately before departure for the United States. As the security clearance process is lengthy, many Somali refugees referred for resettlement to the United States must undergo repeat medical screenings if the required medical exam expires prior to departure.

Figure 5: Medical Assessment of U.S.-bound Refugees

*Class B1 TB, Pulmonary refers to an admissible medical condition in which there is an abnormal screening chest x-ray but negative sputum TB smears and cultures, or to TB diagnosed by the panel physician and fully treated by directly observed therapy.

An overseas medical examination (CDC: Overseas Refugee Health Guidance) is mandatory for all refugees coming to the United States and must be performed according to CDC: Technical Instructions for Panel Physicians. This examination is generally performed approximately 6 months before initial scheduled resettlement; the medical exam may be repeated if resettlement is delayed. Generally, the medical exam is valid for 6 months. However, the medical exam is only valid for 3 months for those with Class B1 conditions. The purpose of this overseas medical examination is to identify applicants with inadmissible health-related conditions. These include, but are not limited to, mental health disorders with harmful behavior, substance abuse, and specific sexually transmitted infections (if untreated). Active tuberculosis (TB) disease (untreated or incompletely treated) is an inadmissible condition of great concern due to its infectious potential and public health implications.

Somali refugees are processed in several countries including, but not limited to, Kenya, Ethiopia, Uganda, and South Africa. The required medical examinations for Somali refugees, including those conducted in Kenya, Ethiopia, Uganda, and South Africa, are conducted by physicians from the International Organization for Migration (IOM). In other countries, examinations may be performed by local panel physicians appointed by the US Embassy.

TB screening and treatment are critical components of the overseas medical examination. All Somali refugees referred for resettlement to the United States are required to be evaluated, and treated if necessary, for TB before coming to the United States. Panel physicians are required to conduct these mandatory screenings in accordance with the CDC: Tuberculosis Technical Instructions for Panel Physicians (TB TIs) using Cultures and Directly Observed Therapy (DOT) for Panel Physicians.

CDC provides the technical oversight and training for all panel physicians, regardless of affiliation. All panel physicians are required to follow the Technical Instructions developed by CDC. In addition, in countries where IOM conducts the examination, refugees also receive a PDMS and PEC.

Information collected during the refugee medical examination is reported to CDC’s Electronic Disease Notification system (EDN) and sent to US state health departments in states where refugees resettle.

Depending on the country of processing, PDMS is conducted approximately 2 weeks before departure for the United States for refugees previously diagnosed with a Class B1 TB, pulmonary condition (abnormal chest x-ray with negative sputum TB smears and cultures, or pulmonary TB diagnosed by panel physician and treated by directly observed therapy). The screening includes a medical history and repeat physical exam. This screening primarily focuses on TB signs and symptoms, and includes a chest x-ray and sputum collection for sputum TB smears (if required). CDC: Tuberculosis Technical Instructions for Panel Physicians, which include more information on pre-departure medical screenings, are available on CDC’s website. Depending on the country of processing, refugees with other chronic or complex medical conditions may receive pre-departure evaluation to assess fitness for travel.

Depending on the country of processing, IOM physicians perform a PEC, or “fit to fly” assessment, within 72 hours (often 24-48 hours) of the refugee’s departure for the United States. PECs are conducted to determine fitness for travel, and to administer presumptive therapy for intestinal parasites and malaria.

In addition to vaccines received through national immunization programs and NGO vaccination campaigns, Somali refugees are likely to receive vaccines as part of the voluntary Vaccination Program for US-bound Refugees. Depending on age, vaccine availability, and other factors, refugees may receive vaccines to protect against hepatitis B, rotavirus, Haemophilus influenzae type b, pneumococcal disease, diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, polio, measles, mumps, and rubella. Hepatitis B surface antigen testing is conducted for refugees receiving hepatitis B vaccine, and positive results are documented on the DS forms. Those with hepatitis B infection require follow-up after arrival in the United States. For those without infection, the hepatitis B vaccine series is usually initiated before departure, and vaccination should be completed after arrival, according to an acceptable ACIP schedule.

All vaccines administered through the Vaccination Program for US-bound Refugees, as well as records of historical (prior) vaccines provided by NGOs and national programs, are documented on the DS-3025 (Vaccination Documentation Worksheet) form. US providers are strongly encouraged to review each refugee’s records to determine which vaccines were administered overseas.

Additional information about the CDC-Bureau for Population, Refugees, and Migration (PRM) Vaccination Program for US-bound Refugees is available on CDC: Immigrant, Refugee, and Migrant Health: Refugee Health Guidance.

Depending on the country of processing and place of birth, Somali refugees may receive pre-departure presumptive albendazole for soil-transmitted helminthic infection, ivermectin for strongyloidiasis, praziquantel for schistosomiasis, and/or artemether-lumefantrine (Coartem®) for malaria. Refugees receive presumptive treatment via DOT at PEC. US providers should refer to each refugee’s PDMS form to determine which therapies for parasitic infections were administered overseas.

Additional information regarding presumptive therapy for parasitic infections can be found here.

Health conditions to consider during post-arrival medical screening

This section describes the burden of specific diseases in the Somali refugee community in the United States. The data sources for this section include the World Health Organization (WHO), IOM, EDN, and data collected during the post-arrival domestic medical screening provided by state health departments.

CDC recommends that refugees receive a post-arrival medical screening (CDC: Guidance for the U.S. Domestic Medical Examination for Newly Arriving Refugees) within 30 days of arrival in the United States. The Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Refugee Resettlement (ORR) supports medical screening for those who have been granted refugee status. The purpose of these comprehensive examinations is to identify conditions for which refugees may not have been screened during their overseas medical examinations and to introduce refugees to the U.S. healthcare system. CDC provides guidelines and recommendations for the domestic medical examination of newly arrived refugees. State refugee health programs determine who conducts the examinations within their jurisdictions. Screening examinations may be performed by health department personnel, private physicians, or federally qualified health centers. Most state health departments collect data from the domestic screening.

Communicable diseases

Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is prevalent worldwide, particularly in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, where many US-bound refugees originate. Between 15% and 40% of those infected with chronic HBV infection develop long-term sequelae; however, the majority of infections are asymptomatic.39 CDC reports that East Africa, including Somalia and countries where Somali refugees are being processed, has a high intermediate prevalence of HBV (5%–7%).40 In one study of adult Somali Bantu refugees (n=707) living in Kakuma, Kenya, PCR analysis detected HBV DNA in 5.5% of serum samples.41

Among 1,234 adult refugee patients screened in Washington State, HBV infection prevalence was substantially higher among Somali speakers (12.4%, n=386) than in other refugee groups.39 Similarly, high HBV infection prevalence has been observed among Somali refugees in Minnesota. From 1999 to 2016, 18,422 Somali refugees received a domestic medical screening, of whom 7% (n=1,240) tested positive for HBsAg, indicating HBV infection.42 Notably, prevalence was highest among adults 45–64 years of age (14%) and lowest among children under 5 (1%).42 Approximately 42% of those not infected with HBV were immune, due to either natural infection or vaccination. A recent study of refugee children from Somalia (n=2,878) found that 3.6% had HBV infection.43 Additionally, researchers found that the majority of cases were in children over 5 years of age, likely reflecting increasing childhood vaccination rates.43

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is also a concern for some US-bound refugees. East Africa, including Somalia, has a moderate prevalence of HCV (1.5%–3.5%).40 However, refugees processed in Yemen may be at increased risk, as Yemen has a high prevalence of HCV (>3.5%).40 Among Somali Bantu refugees residing in Kakuma, Kenya, 0.85% of those tested (n=707) were found to have HCV DNA in their serum.41 Similarly, among Somali refugees resettled in Minnesota between 2004 and 2016, 44 individuals, or roughly 1% of those tested during the domestic medical screening (n=2,978), were positive for HCV [42]. Additionally, refugees ≥45 years of age had the highest prevalence, while those <25 years of age had the lowest prevalence.43

Somalia and countries where Somali refugees are being processed for resettlement to the United States have a high TB burden. Depending on the country, between 1.3% and 5.2% of all new cases are multidrug-resistant, with up to 41% of previously treated TB cases classified as multidrug-resistant. Table 2 describes, in detail, the TB burden in Somalia and key countries of asylum for Somali refugees.

Table 2. Select Data Describing National Tuberculosis Burden in Somalia and Countries of Asylum, 2015

| Country | Incidence Rate (cases per 100,000 population) | % of new Multidrug-resistant (MDR) TB cases | % of MDR TB retreatment cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Somalia | 274 | 5.2 | 41 |

| Djibouti | 378 | 4.3 | 34 |

| Ethiopia | 192 | 2.7 | 14 |

| Kenya | 233 | 1.3 | 9.4 |

| Uganda | 202 | 1.6 | 12 |

| South Africa | 843 | 3.5 | 7.1 |

| Yemen | 48 | 2.3 | 18 |

Source: World Health Organization Tuberculosis Country Profiles, 201644

For additional information regarding TB burden estimates and data in Somalia or countries where Somali refugees have sought asylum or are being processed, see the WHO Tuberculosis Country Profiles.

Before departing for the United States, all refugees are screened for TB and receive treatment, if necessary. As part of the recommended domestic medical screening, newly arrived refugees are also screened for TB. Among 18,308 Somali refugees screened for TB in Minnesota from 1999 to 2016, 43% (7,850) were diagnosed with latent TB infection (LTBI), with prevalence increasing with age. Only 2% (287) were diagnosed with active TB disease (Table 3).42 Overall, the prevalence of active TB disease diagnosed during the domestic medical screening has decreased since 1999 and has remained below 1.0% since 2007.42

Table 3. Tuberculosis Screening and Infection among Somali Refugees to Minnesota, 1999–2016

| Age at U.S. Arrival | Number Screened for TB Infection* | Diagnosed with LBTI N (%) | Diagnosed with Active TB Disease** N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| <5 years | 1,317 | 146 (11%) | 3 (<1%) |

| 5-14 years | 4,081 | 859 (21%) | 39 (1%) |

| 15-24 years | 7,370 | 3,624 (49%) | 145 (2%) |

| 25-44 years | 2,891 | 1,678 (58%) | 45 (2%) |

| 45-64 years | 2,048 | 1,226 (60%) | 39 (2%) |

| ≥65 years | 601 | 317 (53%) | 16 (3%) |

| Overall | 18,308 | 7,850 (43%) | 287 (2%) |

*Tuberculin skin test (TST) or interferon-gamma release assay (IGRA)

**Active TB disease classified as either pulmonary or extrapulmonary

Source: Minnesota Department of Health42

Clinicians should approach TB diagnosis with sensitivity and confidentiality. Individuals who have been diagnosed with active TB disease often face a lifetime of stigma, even after successful treatment completion. Some Somalis may associate TB with stress, loss of faith, God’s will, or sorcery. Standard antibiotic treatments for TB are often combined with traditional remedies, as well as prayer.45

Intestinal parasites

Intestinal parasites are a concern for many recently arrived refugees, including Somali refugees. From 1999 to 2016, 18% (n=15,711) of new Somali arrivals were found to be infected with at least one pathogenic parasite, with Giardia being the most common pathogen (Table 3).42 Infection rates were highest among Somali refugees who arrived from 1999 to 2004 (25%).42

Table 3. Ova and Parasite (O&P) Testing Results among Somali Refugees in Minnesota, 1999–2016

| Age at U.S. Arrival | 1999-2004 Arrival | 2005-2010 Arrival | 2011-2016 Arrival | Total 1996-2016 Arrival |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screened | 5,864 | 6,496 | 3,351 | 15,711 |

| No Pathogenic Parasites Found | 4,410 (75%) | 5,568 (86%) | 2,765 (83%) | 12,947 (82%) |

| Pathogenic Parasite(s) Found | 1,454 (25%) | 928 (14%) | 586 (17%) | 2,764 (18%) |

| Giardia | 305 (5%) | 411 (14%) | 395 (12%) | 1,111 (7%) |

| Trichuris | 507 (9%) | 265 (4%) | 9 (<1%) | 781 (5%) |

| Entamoeba histolytica | 168 (3%) | 171 (3%) | 117 (3%) | 456 (3%) |

| Hymenolepis | 81 (1%) | 75 (1%) | 45 (1%) | 201 (1%) |

| Dientamoeba | 13 (<1%) | 63 (1%) | 56 (2%) | 132 (1%) |

| Other Pathogenic Parasites** | 51 (1%) | 29 (<1%) | 26 (1%) | 98 (1%) |

*Percent of those screened

**Includes Ascaris, Cryptosporidium, Cyclospora, Diphyllobothrium, hookworm, Fasciola, pinworm, Schistosoma, Strongyloides, and Taenia

Source: Minnesota Department of Health42

Soil-transmitted infections (ascariasis, trichuriasis, and hookworm) are common among refugees, and most refugees receive presumptive albendazole treatment prior to departure. Strongyloidiasis and schistosomiasis are of particular concern due to high prevalence, risk of morbidity and mortality, and long latency or infection periods. In a cohort (n=100) of US-bound Somali Bantu refugees, 73% tested seropositive for schistosomiasis, with the majority of cases caused by Schistosoma haematobium. Additionally, 23% tested seropositive for strongyloidiasis, and 21% of all individuals tested seropositive for both schistosomiasis and strongyloidiasis. In this cohort, age was associated with increased risk of infection, with adults (≥18 years of age) being 3 times more likely to be seropositive for schistosomiasis. Additionally, individuals ≥30 years of age were 2.5 times more likely to be seropositive for strongyloidiasis than those <30 years of age.46 Before arrival in the United States, most Somali refugees receive presumptive treatment for Strongyloides (ivermectin) and schistosomiasis (praziquantel). Somali refugees who have lived in or are departing from areas endemic for Loa loa do not receive ivermectin before departure, due to risk of encephalopathy. However, most Somali refugees receive ivermectin, as Somalia and most countries where Somali refugees are processed are not endemic for Loa loa.

Screening data from the Minnesota Department of Health indicate that ~2% of Somali refugees screened (n=4,870) had a positive strongyloides serology after arrival, suggesting the effectiveness of the presumptive treatment program.42 Similarly, there was a noticeable decrease in schistosomiasis prevalence after arrival. At domestic screening, 4% of Somali refugees screened (n=2,578) had positive schistosoma serologies.42 Among Somali refugees, the most common clinical presentation for schistosomiasis is asymptomatic hematuria, either gross or microscopic. However, schistosomiasis can cause a broad range of signs and symptoms. Schistosomiasis should be considered in any individual of Somali descent who has lived in or visited endemic areas and presents with, or is found to have, hematuria or any unexplained symptoms.47

Malaria

Malaria is endemic in the Horn of Africa, including southern Somalia and in countries where Somali refugees are being processed for resettlement. However, prevalence among new arrivals is very low. US-bound Somali refugees are presumptively treated with artemether-lumefantrine (Coartem®) for malaria at PEC, unless contraindicated. Presumptive malaria treatment is documented on each refugee’s PDMS forms.

Non-communicable diseases

Non-communicable diseases (NCDs) are becoming increasingly common among refugees, including Somalis, resettled to the United States. A recent study among refugees of multiple ethnicities resettled to a northeastern US city (n=180) found that more than half (51.1%) of all adult refugees in the study had been diagnosed with at least one chronic NCD, and 9.5% had three or more NCDs.48 Behavioral health diagnoses, such as depression and PTSD (15.0%), and hypertension (13.3%) were the most common NCDs.48 Additionally, more than half of all adult refugees were overweight or obese (54.6%).48 Among Somali patients, researchers reported a high prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors, with a significantly higher prevalence of diabetes mellitus (12.1% vs 5.3%) and prediabetes (21.3% vs 17.2%) than non-Somali patients.49 It is likely that changes in diet and physical activity related to migration and assimilation contribute to the high prevalence of obesity, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular risk factors among Somali immigrants and refugees.49

Anemia is common among Somali refugee children, and can be caused by iron deficiency, parasitic infections, thalassemias, and hemoglobinopathies.43 In a study of refugee children resettled to Colorado, Philadelphia (Pennsylvania), Minnesota, and Washington State from 2006 to 2012, 21.4% (n=2,751) of Somali refugee children <18 years of age were anemic.43 In this study population, anemia was prevalent in both male (20.4%) and female (22.5%) children, and was most common in children <5 years of age.43 Domestic screening results from Minnesota also indicate a high prevalence of anemia among Somali refugees of all ages. From 1999 to 2016, 9,641 male Somali refugees and 9,447 female Somali refugees were screened for anemia. Screening revealed that 19% of all women and 7% of all men were anemic, according to reference ranges determined by WHO.42 Overall, children <5 years of age had the highest prevalence of anemia, with 28% of boys and 25% of girls being anemic. Among adults 25–44 years of age, anemia prevalence differed significantly for men and women, with 2% of men and 29% of women classified as anemic.42

Lead exposure and elevated blood lead levels are a concern among Somali refugee children, both before and after resettlement. Prior to arrival in the US, refugees may have been exposed cottage industries that use lead in an unsafe manner, and lead-containing products such as herbal remedies, cosmetics, or spices.50,51 In the US, refugees, including Somali refugees, often live in substandard housing, where environmental lead may be encountered. Additionally, imported cosmetics, candies, and herbal remedies may contain lead. Among 2,878 Somali refugee children living in Colorado, Minnesota, Washington, and Philadelphia (Pennsylvania), approximately 20% had blood lead levels >5 micrograms per deciliter, while 1.7% of those in this cohort had lead levels ≥10 micrograms per deciliter.43 Within 3–6 months of resettlement, a follow-up blood lead test should be conducted on all refugee children aged 6 months–6 years of age, regardless of the initial screening BLL result. Complete lead screening recommendations for refugee children, and information on potential lead exposures, are provided in the CDC: Screening for Lead during the Domestic Medical Examination for Newly Arrived Refugees. For additional information on lead poisoning and prevention, see the CDC: Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention Program website.

Malnutrition is common in Somali refugees, especially children, due to lack of nutritious food. In a 2011 survey of Somali refugee children (<5 years old) in Bulo Bacte section of Dagahaley refugee camp in Dadaab, global acute malnutrition was observed in 13.4% (n=6,488) of children measuring 67 to <110 cm in height, while severe acute malnutrition was observed in 3.0% of children. Among children measuring 110 to 140 cm in height, 9.8% of those surveyed met criteria for entry into the camp nutritional program.52

In a 2016 study looking at refugee children resettled in Washington State (n=219), researchers found that nearly half of all Somali refugee children (≤10 years of age) had some degree of stunting or wasting indicated in their overseas medical examination.53 Table 4 outlines the nutritional status of Somali refugee children under 5 years of age, as well as children between 5 and10 years of age, before resettlement.

Table 4. Nutritional Status at Overseas Medical Examination among Somali Refugee Children Resettled to Washington State, July 2012–June 2014

| Nutritional Status | <5 years (n=99) | 5–10 years (n=120) | All ages (n=219) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stunting | 26.2% | 15.8% | 20.5% |

| Wasting | 23.2% | 34.2% | 29.2% |

| Healthy Weight | 58.6% | 59.2% | 58.9% |

| Overweight | 8.1% | 4.2% | 5.9% |

| Obesity | 10.1% | 2.5% | 5.9% |

Overall, Somali refugee children have a significantly higher prevalence of wasting and stunting, and lower prevalence of obesity, than low-income children in Washington State.53

Source: Dawson-Hahn et al. (2016)53

Mental health issues may be common in Somali refugees being resettled in the United States. In a community-based cross-sectional survey of adult refugees in Melkadida refugee camp in Southeast Ethiopia, more than one third (38.3%) of those surveyed (n=847) reported symptoms consistent with depression.54 Researchers also found that displacement as a refugee, lack of secure housing, witnessing the murder of family or friends, and other traumatic events were significantly associated with depression among camp residents.54

Mental health issues continue to be a challenge for Somali refugees after resettlement. In a study of Somali refugees living in Finland (n=128), exposure to war trauma and post-resettlement discrimination were associated with greater PTSD and depressive symptoms.55 However, religiosity was found to be protective among older Somali refugees, with war trauma not associated with high levels of PTSD.55 Among adolescents, data collected from Somali refugees resettled in the United States (n=135) indicate that history of trauma and acculturation challenges directly diminish well-being.56

Referrals and immunization

The domestic medical screening allows clinicians to identify individuals who may require additional or specialty care. From 1999 to 2016, 19,280 referrals were given to Somali patients (Table 5).42 Referrals to dental care and primary care providers (including pediatrics) were the most common, followed by ophthalmology/optometry and public health nursing.42 Most often, referrals to public health nursing were related to the management of LTBI.42

Table 5. Clinical Referrals among Somali Refugees to Minnesota, 1999–2016

| Referral* | Males (n=9,768) N (%) | Females (n=9,512) N (%) | Overall (n=19,280) N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dentist | 5,007 (51%) | 5,182 (54%) | 10,189 (53%) |

| Primary Care | 4,790 (49%) | 5,015 (53%) | 9,805 (51%) |

| Public Health Nurse | 885 (9%) | 700 (7%) | 1,585 (8%) |

| Ophthalmology/ Optometry | 704 (7%) | 801 (8%) | 1,505 (8%) |

| Obstetrics/ Gynecology | N/A | 393 (4%) | N/A |

| Gastroenterology | 104 (1%) | 79 (1%) | 183 (1%) |

| Infectious Disease | 65 (1%) | 51 (1%) | 116 (1%) |

| Audiology (Hearing) | 60 (1%) | 55 (1%) | 115 (1%) |

| Mental Health | 34 (<1%) | 34 (<1%) | 68 (<1%) |

*Patients may receive more than one referral

Source: Minnesota Department of Health42

Immunization is generally well received by refugee groups, including Somalis. In recent years, some Somali community members in the United States have expressed concern about the disproportionately high number of Somali children enrolled in early childhood special education programs for autism. Community members were drawn to information promoting the misconception that autism was linked to the MMR vaccine. Additionally, anti-vaccine proponents reached out directly to the Somali community, bolstering fears that MMR vaccine caused autism, and encouraging Somali parents to refuse vaccination.

From 2004 to 2010, MMR vaccine coverage among Somali children in Minnesota dropped from 91% to 54%.57 More recently, coverage rates have begun to improve, and the majority of new Somali arrivals support MMR vaccination.14 In early 2017, Minnesota health officials reported an outbreak of measles in the Minneapolis-St. Paul metropolitan area. As of August 2017, Minnesota had recorded 79 confirmed measles cases. Of those, 64 were in Somali Minnesotans, and most (n=74) were in unvaccinated or undervaccinated individuals.58

Clinicians who administer childhood vaccines should be respectful of parent concerns, and should approach discussions about immunization with cultural humility and empathy.59 Clinicians should also be aware that vaccination decisions may be made outside a clinical setting. Somali parents may be influenced by community members, including persons they may not know personally but who belong to and identify with the local Somali community. Clinicians should aim to build trust with patients and their families, as well as build relationships with leaders in the Somali community.14

Additional Resources for Providers:

- Refugee Health Vancouver. Somalia Cultural Profile. 2011 [cited 2016 December]

- Central Intelligence Agency. The World Factbook: Somalia. [cited 2016 August]; Available from: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/resources/the-world-factbook/geos/so.html.

- Van Lehman D, Eno O. The Somali Bantu: their history and culture. Center for Applied Linguistics. 2003.

- United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. A study on minorities in Somalia. 2002. Available from: http://reliefweb.int/report/somalia/study-minorities-somalia.

- Hill M. No redress: Somalia's forgotten minorities. Minority Rights Group International. 2010.

- EthnoMed. Somali Cultural Profile. University of Washington. 2009.

- NYS Statewide Language Regional Bilingual Education Resource Network at New York University. Somalia: Language & Culture. 2012.

- Ethnologue: Languages of the World. Somalia. [cited 2016 September]; Available from: http://www.ethnologue.com/country/SO/languages.

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Somali Distance Education and Literacy. [cited 2016 September]; Available from: http://litbase.uil.unesco.org/?menu=4&letter=S&programme=100.

- MacKinnon H. Education in emergencies: the case of the Dadaab refugee camps. Centre for International Governance Innovation Policy Brief 47. 2014 July.

- U. S. Department of State. Somalia 2014 International Religious Freedom Report. 2014.

- Abrar FA. Personal communication. 2018.

- Maloof PS, Ross-Sheriff F. Muslim Refugees in the United States: A Guide for Service Providers. Washington DC: Center for Applied Linguistics Culture Profile No. 17. 2003 September.

- Ashkir A, Mohamed F. Vaccine Hesitancy in the Somali Community. Washington State Refugee Health Conference. 2017.

- Sheikh H, Healy S. Somalia's Missing Million: The Somali Diaspora and its Role in Development. United Nations Development Program. 2009.

- Connor P, Krogstad JM. 5 facts about the global Somali diaspora. 2016 June 1; Available from: http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/06/01/5-facts-about-the-global-somali-diaspora/

- Minnesota Department of Health. Somali Refugee Arrivals to Minnesota, 1999–2016 (unpublished data). 2017.

- Hollingsworth S. Personal communication. 2017.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Somalia. [cited 2016 October]; Available from: http://www.unhcr.org/afr/somalia.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Horn of Africa Somalia Situation. Available from: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations/horn.

- Dadaab camp closure: Repatriation of Somali refugees 'fails to meet international standards'. British Broadcasting Corporation. September 15, 2016; Available from: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-africa-37369707.

- Yackley AJ. Kenya will close world's biggest refugee camp this year. Reuters. 2016 May.

- Trapped in Yemen Al Jazeera. January 14, 2015.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Yemen insecurity sees food supplies running out at Kharaz refugee camp. 2015 June 19; Available from: http://www.unhcr.org/en-us/news/briefing/2015/6/558417ff9/yemen-insecurity-sees-food-supplies-running-kharaz-refugee-camp.html.

- Refugee Processing Center. Admissions Reports. 2010–2016.

- Refugee Processing Center. Arrivals by State and Nationality. 2010–2016.

- International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies. Health, nutrition, water, sanitation and hygiene in Dadaab refugee camp. 2016 May 25.

- World Health Organization. Somalia Statistics Summary. 2015.

- World Bank. World Development Indicators, Somalia. 2015.

- Jaffer FH, Guy S, Niewczasinski J. Reproductive health care for Somali refugees in Yemen. Forced Migration Review 19; 2004 January.

- Extending Service Delivery Project and USAID. Somali refugee attitudes, perceptions, and knowledge of reproductive health, family planning, and gender-based violence. 2008.

- UNICEF. Eradication of Female Genital Mutilation in Somalia. 2004. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/somalia/SOM_FGM_Advocacy_Paper.pdf.

- Al-Dhayi B. Towards abandoning female genital mutilation/cutting in Somalia for once, and for all. UNICEF. 2013.

- UNICEF. FGM/C prevalence among girls and women ages 15 to 49 years. February 2016.

- World Health Organization. Female genital mutilation (FGM). [cited 2016 September]; Available from: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/fgm/prevalence/en/.

- United Nations Population Fund. Female genital mutilation (FGM) frequently asked questions. 2015; Available from: http://www.unfpa.org/resources/female-genital-mutilation-fgm-frequently-asked-questions.

- Narruhn RA. Perinatal Profile for Patients from Somalia. EthnoMed. 2008.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Dadaab SGBV Update. Sexual and Gender Based Violence Dashboard. 2015.

- Terasaki G, Desai A, McKinney CM et al. Seroprevalence of hepatitis B infection among immigrants in a primary care clinic: a case for granular ethnicity and language data collection. J Immigr Minor Health 2017 August;19(4):987–90.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. CDC Health Information for International Travel . 2016; Available from: https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/page/yellowbook-home.

- Mixson-Hayden T, Lee D, Ganova-Raeva L, et al. Hepatitis B virus and hepatitis C virus infections in United States-bound refugees from Asia and Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2014 June;90(6):1014–20.

- Minnesota Department of Health. Domestic Medical Screening Data, 1999–2016 (unpublished data). 2017.

- Yun K, Matheson J, Payton C, et al. Health profiles of newly arrived refugee children in the United States, 2006–2012. Am J Public Health 2016 Jan;106(1):128–35.

- World Health Organization. Tuberculosis country profiles. 2016; Available from: http://www.who.int/tb/country/data/profiles/en/.

- Citrin D, Somali Tuberculosis Cultural Profile. EthnoMed. 2006.

- Posey DL, Blackburn BG, Weinberg M, et al. High prevalence and presumptive treatment of schistosomiasis and strongyloidiasis among African refugees. Clin Infect Dis 2007 Nov 15;45(10):1310-5.

- Summer AP, Stauffer W, Maroushek SR, Nevins TE. Hematuria in children due to schistosomiasis in a nonendemic setting. Clin Pediatr (Phila), 2006 Mar;45(2):177–81.

- Yun K, Hebrank K, Graber LK, et al. High prevalence of chronic non-communicable conditions among adult refugees: implications for practice and policy. J Community Health 2012 Oct;37(5): 1110–8.

- Njeru JW, Tan EM, St Sauver J, et al. High rates of diabetes mellitus, pre-diabetes and obesity among Somali immigrants and refugees in Minnesota: A retrospective chart review. J Immigr Minor Health 2016 Dec;18(6):1343–9.

- Binns, H.J., D. Kim, and C. Campbell, Targeted screening for elevated blood lead levels: populations at high risk. Pediatrics, 2001. 108(6): p. 1364-6.

- Zabel, E.W., M.E. Smith, and A. O'Fallon, Implementation of CDC Refugee Blood Lead Testing Guidelines in Minnesota. Public Health Reports, 2008. 123(2): p. 111-116.

- Polonsky JA, Ronsse A, Ciglenecki I, et al. High levels of mortality, malnutrition, and measles, among recently-displaced Somali refugees in Dagahaley camp, Dadaab refugee camp complex, Kenya, 2011. Confl Health 2013 Jan 22;7(1):1.

- Dawson-Hahn EE, Pak-Gorstein S, Hoopes AJ, Matheson J. Comparison of the nutritional status of overseas refugee children with low income children in Washington state. PLoS One 2016 Jan 25;11(1):e0147854.

- Feyera F, Mihretie G, Bedaso A, et al. Prevalence of depression and associated factors among Somali refugee at Melkadida camp, Southeast Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry, 2015 Jul 24;15:171.

- Molsa M, Kuittinen S, Tiilikainen M, et al. Mental health among older refugees: the role of trauma, discrimination, and religiousness. Aging Ment Health 2017 Aug;21(8):829–37.

- Lincoln AK, Lazarevic V, White MT, Ellis BH. The impact of acculturation style and acculturative hassles on the mental health of Somali adolescent refugees. J Immigr Minor Health 2016 Aug;18(4):771–8.

- Gahr P, DeVries AS, Wallace G, et al. An outbreak of measles in an undervaccinated community. Pediatrics 2014 Jul;134(1):e220–8.

- Minnesota Department of Health. Measles (Rubeola). 2017 [cited 2017 July 31]; Available from: http://www.health.state.mn.us/divs/idepc/diseases/measles/#1.

- Vaccine Confidence Project. USA: Cultural approach to vaccine hesitancy essential for ethnic communities. 2016 December 2; Available from: http://www.vaccineconfidence.org/usa-cultural-approach-to-vaccine-hesitancy-essential-for-ethnic-communities/.