Health Care and Birth Outcomes in Afghanistan

OB-GYN Care for Afghans: A Toolkit for Clinicians

On this page:

General Afghanistan health system information

Prenatal care in Afghanistan

Labor, delivery, and postpartum care in Afghanistan

Infant and maternal outcomes in Afghanistan

References

- Most Afghans don’t have access to primary or preventive care in Afghanistan due to the instability of the health system after decades of conflict.1,2

- Afghanistan has very high rates of infant mortality (43 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2021)3 and maternal mortality (620 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 2020).4

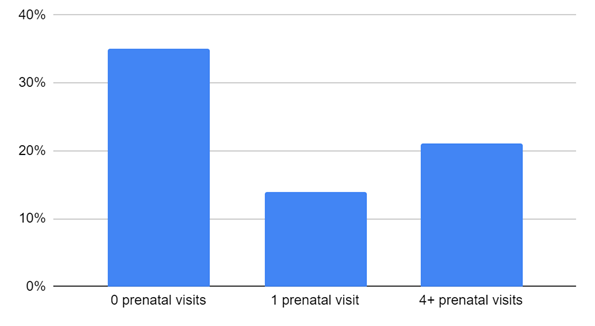

- The 2018 Afghanistan Health Survey reported 35% of female respondents had no prenatal visits, 14% had one prenatal visit, and 21% had four or more prenatal visits. 41% of women reported giving birth at home. Over half reported receiving no postpartum care.5

General Afghanistan health system information

Afghanistan’s healthcare system is unstable, having only 2.5 healthcare workers per 10,000 people in 2020.1,6 Accessing care can be difficult and time-intensive, and most Afghans, especially women, lack access to primary or preventive care. The health system consists of public and private hospitals.1,2 However, around 90% of Afghans live below the poverty line, and many cannot afford private hospitals.7 Public hospitals are free but busy and generally have limited resources and staff. Private hospitals are expensive but provide high-quality care and are preferred for Cesarean sections (C-sections).

Prenatal care in Afghanistan

Women in Afghanistan are encouraged to have eight prenatal visits (recently increased from four visits).5 However, the 2018 Afghanistan Health Survey showed that approximately 35% of survey respondents8 had no prenatal visits, 14% had one prenatal visit, and 21% had four or more prenatal visits (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Number of prenatal visits attended by ever-married women 12 – 49 years of age who were pregnant at the time of the survey or had a live birth in the two years preceding the survey5

Labor, delivery, and postpartum care in Afghanistan

Forty-one percent of respondents to the 2018 Afghanistan Health Survey reported delivering at home and being aided by a trained birth attendant, relative, neighbor, or friend. For those who deliver in hospitals in Afghanistan, the experience differs between public and private hospitals. In both settings, births are attended by midwives or nurses, usually with an obstetrician available for consultation. In public hospitals, family members are not allowed to accompany patients, and pain management is usually not offered due to lack of resources. To relieve labor pains, women may be given holy water or hot milk and read aloud specific passages of the Quran. In private hospitals, family members may accompany patients, and epidurals are the primary method of pain management. Pitocin is generally not available, but misoprostol may be administered sublingually to help labor progress.9

After delivery, babies are examined and given vitamin K. The length of hospital stay varies by hospital and delivery type. For vaginal deliveries, patients generally stay for 6-24 hours in a public hospital and 24 hours in a private hospital. These timelines may be shortened due to crowding in public hospitals and high costs in private hospitals. After C-sections, patients may stay in the hospital up to 72 hours in both public and private hospitals. Circumcision for male babies typically takes place at a medical facility, but does not happen on a standard timeline. Female genital mutilation or cutting is not practiced in Afghanistan. Four postpartum follow-up visits are standard, though some patients may not receive postpartum care due to prohibitive costs or other barriers.9 Over half of respondents in the 2018 Afghanistan Health Survey reported they had received no postpartum care.5

Infant and maternal outcomes in Afghanistan

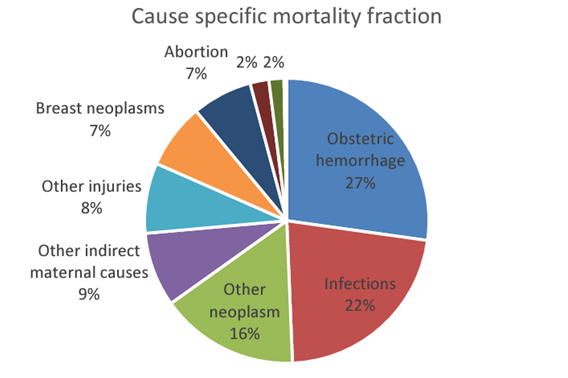

Afghanistan has very high infant mortality (43 deaths per 1,000 live births in 2021)3 and maternal mortality rates (620 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 2020).4 For comparison, in 2021 in the U.S., the infant mortality rate was 5.4 deaths per 1,000 live births10 and the maternal mortality rate was 32.9 deaths per 100,000 live births.11 The 2018 Afghanistan Health Survey reported that leading causes of death among females 12-49 years were infection (24%), obstetric hemorrhage (23%), and abortion complications (19%). Other causes of death (34%) included neoplasm other than breast cancer, breast cancer, pregnancy-induced hypertension, and assault (Figure 2).5

Figure 2: Mortality in women 12-49 years of age5

The unstable environment, poverty, and violence also contribute to high rates of postpartum depression. One study found that Afghanistan has the highest prevalence of postpartum depression, 61%, of the 80 countries studied.12 Lack of prenatal and postnatal care access and the common practice of not seeking care unless there is a problem, especially in rural areas, contributes to these outcomes.

During the decades prior to the 2021 Taliban takeover, maternal and child health outcomes had improved due to health system improvements, increased use of contraception, lower fertility rates, greater immunization coverage, and higher utilization of prenatal and postnatal care.9 However, changes following the Taliban takeover including reduced access to education and healthcare, especially for women, are expected to increase adverse maternal outcomes. In 2023, it was reported that more than 90% of healthcare facilities were at risk of closure, leading to an estimated 4.8 million unattended pregnancies and 51,000 maternal deaths between 2021 and 2025.13

References

- World Health Organization. (2022b, January 24). Afghanistan’s health system is on the brink of collapse: urgent action is needed. https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/afghanistan-s-health-system-is-on-the-brink-of-collapse-urgent-action-is-needed

- Ehsan, K. (2023b, June 13). Afghanistan’s Healthcare Crisis | Special Report. KabulNow. https://kabulnow.com/2023/06/health-service-crisis-in-afghanistan/

- Unicef. (2021). Afghanistan (AFG) - Demographics, Health & Infant Mortality - UNICEF DATA. Unicef Data. https://data.unicef.org/country/afg/

- Afghanistan. (n.d.). World Bank Gender Data Portal. https://genderdata.worldbank.org/countries/afghanistan/

- Afghanistan Health Survey 2018. (2019). KIT Royal Tropical Institute. https://www.kit.nl/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/AHS-2018-report-FINAL-15-4-2019.pdf

- Density of physicians (per 10 000 population). (n.d.). Data.who.int; World Health Organization. https://data.who.int/indicators/i/217795A

- International Rescue Committee. (2022, December 22). Afghanistan: An entire population pushed into poverty | International Rescue Committee (IRC). Www.rescue.org. https://www.rescue.org/article/afghanistan-entire-population-pushed-poverty

- Ever-married women 12-49 years of age with a live birth in 2 years preceding survey or pregnant at the time of survey.

Afghanistan Health Survey 2018. (2019). KIT Royal Tropical Institute. https://www.kit.nl/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/AHS-2018-report-FINAL-15-4-2019.pdf - Afghan Arrivals: Pre- and post-natal care. (2022, October 12). Minnesota Department of Health. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aQKXoBcSbaM&feature=youtu.be

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, September 10). Infant mortality. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/maternal-infant-health/infant-mortality

- Hoyert, D. (2023, March 16). Maternal Mortality Rates in the United States, 2021. Www.cdc.gov; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/maternal-mortality/2021/maternal-mortality-rates-2021.htm

- Wang, Z., Liu, J., Shuai, H., Cai, Z., Fu, X., Liu, Y., Xiao, X., Zhang, W., Krabbendam, E., Liu, S., Liu, Z., Li, Z., & Yang, B. X. (2021). Mapping global prevalence of depression among postpartum women. Translational Psychiatry, 11(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01663-6

- Hamdana, A. H., Ahmad, S., Shahzil, M., Rashid, M., Afif, S., Furqana, A. Q., & Awan, A. R. (2023). Maternal health in Afghanistan amidst current crises – A neglected concern. Ethics, Medicine and Public Health, 30, 100932. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemep.2023.100932